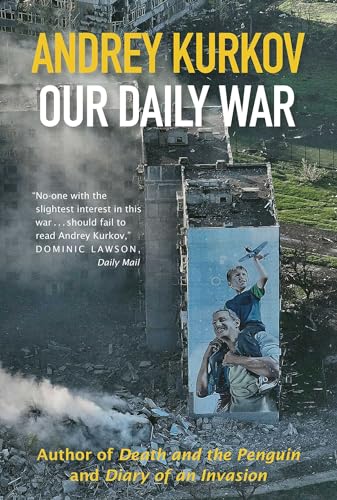

Book Review: Our Daily War by Andrey Kurkov

Review by Janet Gunn, BEARR Trustee

Andrey Kurkov is probably the best-known living Ukrainian writer outside his own country, and especially in the UK. His ‘Death and the Penguin’, set in the aftermath of the break-up of the Soviet Union, was probably the first to catch the attention of British readers. Many followed, most recently ‘Diary of an Invasion’ (2022) and many wartime articles published in the Guardian and other British newspapers. His novel ‘Grey Bees’ (2018), a story set in the Donbas and Crimea after the war began in 2014, was reviewed in the August 2021 BEARR Trust newsletter.

Kurkov is a Ukrainian and a Ukrainian writer, but he was born in Leningrad (now St Petersburg) in Russia and writes in Russian, his mother tongue. He is sometimes criticised in Ukraine for not writing in Ukrainian, but he explains that it is not his native language. So his books are now only published in Ukraine after translation into Ukrainian. And many other languages. Fortunately for us he has a brilliant translator into English, and the prose doesn’t feel like a translation at all. His original Russian texts are not published in Russia now.

Kurkov, like many of his compatriots in the arts and cultural fields, has been working ceaselessly to bring to the rest of the world awareness of Ukraine’s unique culture and identity and to ensure that people far away do not forget what is happening to the country. Apart from writing, he has travelled very widely since the full-scale invasion and his initial period of “exile” in a rural village after he left Kyiv, where he now lives again. He said at an event in London in April this year, to launch the English translation of another book published in the UK, The Silver Bone, a novel written before the full-scale invasion, that he is unable at present to write fiction. So he writes about his country under attack and its suffering, and above all about its people.

The book is dedicated to “the soldiers of the Ukrainian army”. It has a copious index with entries which include not just names of people and places but matters such as ‘watermelons’ (for which Kherson is particularly famous) and ‘recycling of Russian books into waste paper’ – which speaks for itself. It is over 400 pages long in ebook format (276 pages in hardback) but each ‘chapter’ or entry has its own date, like a diary, and stands by itself in a way. It follows the course of the war starting from August 2022 up to February 2024. Despite its diary-like format each entry is not necessarily about him and his family, but a commentary on all kinds of aspects of Ukrainian life and culture, gossip, observations on international and Ukrainian politics and just about any topic you can think of. Kurkov does not recoil from sensitive issues such as treachery among politicians or the general public when they try to help Russia, but also covers much lighter topics, and all with his characteristic compassion and gentle irony. The last entry mentions the appearance since the invasion of large numbers of green parrots in Chernivtsy, a city in the south of Ukraine and less prone to bombardment than most. The parrots are thought to be pets released before their owners fled abroad in 2022. Readers who live in London will commiserate.

On 9 February 2023 Kurkov writes:

“We are standing on the edge of a precipice. At the bottom is the hot lava in which our happy, pre-war life was incinerated and into which high-rise homes, churches and universities are still falling – a gaping furnace that has already destroyed hundreds of thousands of lives. To be a Ukrainian today is to suffer this terrible illness, with which we have been infected intentionally. We may feel we are healthy, but there are no entirely healthy people in war or close to war. Like a disease, war takes control of your behaviour, your thoughts and even your feelings. War starts to think for you. It makes decisions for you. I too suffer from this illness and I have not sought treatment. I am used to it. I am not a soldier or a doctor, but I am a citizen of Ukraine. I love my country and my former life. When confronted with the fact of war, I had to choose a front for myself. I needed to feel that I was doing something useful. So every day I write and think about the war.”

In an entry in 2023 he wrote that he supposed that the war would not end until 2024. Sadly, as 2024 draws to a close it is unlikely to end this year.

Our Daily War is Published by Open Borders Press, London, 2024.