Civil society and the fight against migrant rights violations in Russia: a review of Michael Borodin’s Convenience Store (2022)

“The work of such organisations [Alternativa and Civic Assistance Committee] is simply essential. In most cases, they are the only ones who can help.”

– Michael Borodin, dir. Convenience Store (2022)[1]

Still from Convenience Store. Source: https://www.kinopoisk.ru/film/1311130/stills/

In November 2016, Fatima Musabaeva and Aliya Musabaeva, two sisters from Kazakhstan, and Gulzhanar Nazanova and Bakiya Kasimova from Uzbekistan brought the “Golyanovo Slaves” case to the European Court of Human Rights. The claimants constituted four of the twelve trafficked migrants at the centre of the case, who, in 2012, were freed by the civil society activists Alternativa after a decade of captivity in a Moscow grocery store. Despite repeated attempts to bring the case to the Russian courts, the shop-owner, Zhansulu Istanbekova, has never been prosecuted. Her chain of stores remains open to this day.

The Golyanovo case is the highest profile of countless human trafficking cases that served as the inspiration for Uzbek director Michael Borodin’s bleak yet powerful debut, Convenience Store (Продукты 24, 2022). Receiving its international premiere at the 2022 Berlinale, the film follows Mukhabbat, an Uzbek migrant enslaved by Moscow store owner Zhanna.

With the first 45 minutes of action taking place entirely within the walls of the run-down store, the audience is forcibly immersed into the joyless lived experience of the shopworkers. Expertly aided by Ekaterina Smolina’s neon-tinged yellow cinematography, which film critic Tara Judah describes as “casting a visual stain across [the] protagonist and her misery”, we are witness to the violent physical and psychological abuse meted out to Zhanna’s employees. In one devastating chain of events, an attempted escape results in one of the workers being nailed to the floor.

However, action is perhaps the wrong word to describe the events of the film. These scenes of violence are almost secondary to the more subtle depictions of Mukhabbat’s mundane reality under Zhanna’s watchful eye. Instead, it is the repetitive nature of her daily existence – sorting through rotten vegetables, dealing with insolent customers – that shines a light on the relentless emotional torture of being held captive.[2]

Borodin handles the subject matter delicately, never veering into ‘trauma porn’ or glorifying the brutality for shock-entertainment. In fact, the scenes of physical and sexual violence occur largely off-screen, either in a neighbouring room, just out-of-shot of askew camera angles, or through the grainy screens of the shop’s CCTV cameras.

Mukhabbat. Still from Convenience Store. Source: https://www.kinopoisk.ru/film/1311130/stills/

The second half of the film offers little in the way of hope, despite Mukhabbat breaking free with the help of a group of activists who storm the shop. On returning back to Uzbekistan, she reunites with her mother and accepts an underpaid job picking cotton. Yet Mukhabbat is motivated by one thing only: to be reunited with her son who remains captive in Moscow. In the heart-breaking final scenes, and driven by emotional blackmail, Mukhabbat convinces the fieldworkers to join her back at Zhanna’s store.

This excruciating picture of the perpetuated cycle of trauma and trafficking lies at the crux of the film, though to what extent this is the norm is unknown. In conversation with Borodin, he confirms his film’s conclusion was based on a real case. However, in his experience, most ‘recruiters’ tend not to be victims of the trafficking cycle themselves.

“It is difficult to judge how cyclical it is, but it is evidently a vicious process,” Borodin tells me. “People go by themselves to seek work and get into these situations. I think it is both a systemic problem, as well as a private one.”[3]

Still from Convenience Store. Source: https://www.kinopoisk.ru/film/1311130/stills/

In spite of this unbearably bleak outlook, Convenience Store does offer at least one answer to the question of how best to combat the cycle of abuse within forced labour migration: volunteer activists. Based on the work of the non-profit organisation Alternativa, as well as the neighbours and everyday citizens who were involved in the liberation of the trafficked migrants at the Golyanovo store, there are glimmers of hope here in the form of civil society. Much like in Andrei Zvyagintsev’s missing-child drama Loveless (Нелюбовь, 2017), which similarly serves as a damning indictment of a contemporary society “where neither the state nor the police really care about people”, it is the work of civil society organisations (CSOs) such as Alternativa, or in the case of Loveless, Liza Alert, that provide a redeeming presence in today’s Russia.[4]

Borodin reiterated this sentiment in a Q&A organised by the Harriman Institute in February 2023. Venerating the work of Alternativa and the Civic Assistance Committee – the Moscow-based NGO that spent several years on the Golyanovo case – he highlighted the necessity of voluntary organisations in protecting the rights of labour migrants. Noting the lack of institutional assistance available, he stated:

“I believe the work of such organisations is simply essential. Because in most cases, people have nowhere else to turn. They are the only ones who can help. If the state does not want to recognise you, and the police would rather arrest than help you, where else can a person go?”[5]

Indeed, BEARR has personally seen the lengths that both individuals and CSOs will go to to provide support and seek justice for workers like Mukhabbat, despite both the bureaucratic machine that stands before them and the risks that accompany being labelled a foreign agent.

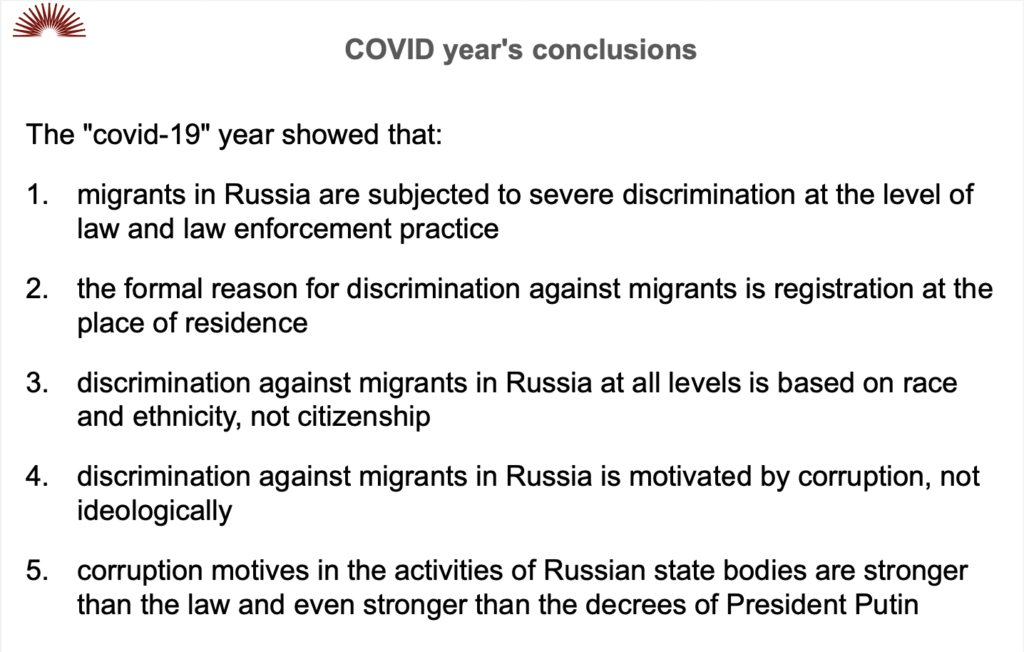

As part of a series of webinars in the summer of 2020, BEARR invited several civil society representatives from our region to speak on the issues facing migrant workers during the pandemic. Throughout their presentations, the participants shed light on the increased discrimination towards, and the vast cases of human rights violations against, migrant workers in Russia. Most appallingly was the formalisation of this discrimination into law. A Moscow-based NGO providing legal assistance to migrant workers reported that fines for not wearing masks were almost exclusively imposed on “persons of non-Slavic appearance”. Moreover, there were several laws passed that legitimated this ethnic discrimination, with migrant workers from Belarus, Armenia and Moldova afforded certain privileges that their Central Asian counterparts were not.

Conclusions from NGO work and research during COVID-19. Presented at BEARR’s 2020 Webinar.

Having seen the ongoing and urgent need for these NGOs to continue their work, and further guided by the responses to our CSO surveys, in 2022 BEARR’s Small Grants Scheme specifically focussed on projects that would improve the social welfare and wellbeing of labour migrants and their families. One of our grantees in Kyrgyzstan, Insan-Leilek, has spent much of the last year providing pro-bono legal, medical and psychotherapy services to female Kyrgyz migrants in Ekaterinburg. Aside from conducting broad information campaigns about the rights and services available to migrant workers in Russia, they have also been tackling the significant increase in gender-based violence within the community – a consequence of both lockdown measures and economic sanctions which have resulted in job losses and business closures often affecting migrant workers first.

Convenience Store persuasively captures this normalised and overt nature of discrimination towards Uzbek workers in contemporary Russia. Hostile customers regularly berate Mukhabbat and her co-workers, and in one case turn a blind eye to a beating taking place in the back room. As in real life, however, the racist and xenophobic treatment of Central Asian migrants is depicted not just as a societal problem, but an institutional one, too. The fate of the aforementioned escapee is in large part due to a pair of corrupt policemen. Paid off by Zhanna, they bring the worker back to the store, with a warning that she “needs to watch them better”.

Migrating to Russia from Uzbekistan when he was 22-years-old, Borodin seems well placed to tackle these recurring themes in his debut. However, during the Q&A at the Harriman Institute, Borodin refuted this, stating that as a quarter Uzbek he doesn’t consider himself entitled to speak for the Uzbek experience at large. Instead, it was the necessity of giving this case a larger platform on the global stage that ultimately led to the film being made. “When I put the idea to my producer,” Borodin described, “he responded: this film must be made.” Collaborating closely with the lawyers from the case, and after conducting several years of painstaking research, Borodin’s film was finally given its international release almost a year ago today.

Arguably, Borodin’s long-term artistic endeavours – to nurture a domestic auteur cinema in 21st century Uzbekistan – also played a part in the making of the film. Influenced by several schools of cinema, from China and Taiwan to the Yakut films of the Sakha Republic, Convenience Store can be seen as a concerted effort to centre minority groups on the big screen and combat the lack of Central Asian representation in contemporary Russian cinema. “Migrants are almost always portrayed decoratively or comically – they are an afterthought,” said Borodin during the Q&A. It is this overarching mission that has led him and his production team to set up a film school for budding young directors in Uzbekistan.

In light of this, Borodin is undoubtedly successful in giving Mukhabbat agency. Naturally, his debut does not encompass the myriad experiences of Uzbeks in Russia, but his protagonist is not portrayed as merely a victim or a trauma survivor for viewers to sympathise with. She is a wife, a worker, a mother, a daughter, a woman – one who has to make a choice that no parent should ever be faced with. Viewers may not agree with her actions, but we are at least privy to the decisions that lead her there.

Furthermore, while Borodin disputes that he can speak for all Uzbeks, arguing that he has had a somewhat easier time than others thanks to his appearance and surname, there is still an element of autobiography here. As Tara Judah points out, “The story is personal for Borodin, who came to Russia from Uzbekistan in the early 2010s and felt immediately deprived of his civil rights. Unable to obtain a resident permit, mistrusted for holding an Uzbek passport and turned away from official employment, his story is one of systemic socio-economic discrimination.”

With BEARR’s partners among several CSOs that continue to offer vital support and assistance to migrant workers, and with directors like Michael Borodin attempting to tackle the dominant narratives in the cultural sphere, there is hope that these institutional downfalls will one day become a thing of the past.

As importantly, and while Mukhabbat’s experience is without question situated in the specificity of the Russian context, this is not a story unique to Russia. This is a global phenomenon. In recent days we have all watched in horror at the events unfolding in Türkiye and Syria, and the past year has been permanently marked by the crises in Afghanistan and Ukraine. Knowing that the ongoing consequences of climate catastrophe will further force people from the global south northwards, we can no longer sit back in the comfort of Europe’s heavily restricted borders. This is not a ‘migrant crisis’ or a ‘refugee crisis’, it is a crisis of empathy that we must confront today.

Alexia Claydon

February 2023

Convenience Store screened at the Lexi Cinema on 29 November 2022 as part of the London Migration Film Festival

With many thanks to

- Director Michael Borodin, for his film, and his time spent answering my questions

- London Migration Film Festival for screening the film

- The London Migration Film Festival panellists – Lily Parrott, LMFF; Professor Madeleine Reeves, University of Oxford; Shalini Patel, lawyer; Dr. Angeliki Argyrou, clinical psychologist – for their research and work on the issues facing labour migrants and victims of human trafficking

- Dr. Tatiana Efremova and Professor Mark Lipotevsky at the Harriman Institute, University of Columbia, for inviting me to their Q&A with Michael Borodin.

[1] Michael Borodin, quote from an online Q&A at the Harriman Institute, University of Columbia, 7 February 2023. Translated by author.

[2] Discussed during the post-screening panel at the London Migration Film Festival, November 2022.

[3] Translated by author

[4] Quote from J. Romney, ‘The Lost Boy’, Sight and Sound, (March, 2018), p.36, pp.33-36.

[5] Translated by author

Sources and Further Reading

Golyanovo Case

“Golyanovo Slaves” Case Reached Strasbourg https://refugee.ru/en/news/delo-golyanovskih-rabov-doshlo-do-strasburga/

New Slavery Victims in Golyanovo https://refugee.ru/en/news/nouvelles-victimes-d-esclavage-a-golyanovo/

Redress for People Trapped in Forced Labor: Civic Assistance Committee (Russian Federation) https://www.ohchr.org/en/about-us/funding-and-budget/trust-funds/united-nations-voluntary-trust-fund-contemporary-forms-slavery/30th-anniversary-united-nations-voluntary-trust-fund-contemporary-forms-slavery/profiles-eastern-europe-countries

Central Asian Migrants Describe Beatings, Ill-Treatment In Russian Market ‘Zachistki’ https://www.rferl.org/a/russia-raids-migrant-labor-markets/25070219.html

Activists Say Migrants Were Held as Slaves in Grocery Store https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2012/10/31/activists-say-migrants-were-held-as-slaves-in-grocery-store-a19069

Slaves of Moscow: https://wordswithoutborders.org/read/article/2014-07/slaves-of-moscow/

Produkty grocery store lawsuit (re modern slavery in Russia) https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/latest-news/produkty-grocery-store-lawsuit-re-modern-slavery-in-russia/

«Хозяин сказал: если позвоню в скорую, мне эту руку отрежут» https://novayagazeta.ru/articles/2016/05/12/68560-171-hozyain-skazal-esli-pozvonyu-v-skoruyu-mne-etu-ruku-otrezhut-187

Michael Borodin’s Convenience Store (2022)

Interview: Michael Borodin on Convenience Store https://eefb.org/interviews/michael-borodin-on-convenience-store/

Michael Borodin Talks Shop About His Berlin Pic ‘Convenience Store’ https://variety.com/2022/film/spotlight/michael-borodin-berlin-1235183819/

‘Convenience Store’ Review: Ripped-From-Headlines Drama Uncovers Modern Slaves in Plain Sight https://variety.com/2022/film/reviews/convenience-store-review-produkty-24-1235183946/

Review: Convenience Store https://www.cineuropa.org/en/newsdetail/421947/

Video Interview: Michael Borodin, Director of Convenience Store https://www.cineuropa.org/en/video/422184/

‘Convenience Store’: Berlin Review https://www.screendaily.com/reviews/convenience-store-berlin-review/5167745.article

Andrei Zvyagintsev’s Loveless (2017)

J. Romney, ‘The Lost Boy’, Sight and Sound, (March, 2018), pp.33-36.

R. Thomas, ‘A missing boy illustrates Russia’s moral rot in Oscar-nominated ‘Loveless’: Review’, The Capital Times, (2018) https://madison.com/ct/entertainment/movies/a-missing-boy-illustrates-russias-moral-rot-in-oscar-nominated-loveless/article_722c4c14-af81-55eb-bc7a-5214e129be6f.html